SEEk the alternatives

“Peace is not just the absence of conflict; peace is the creation of an environment where all can flourish […]” – N. Mandela

Cold and Calculated: Canadian Banks are Making a Killing off War Crimes and Genocide

By: Seek The Alternatives (STA) – Community-Based Grassroots Organization

June 9, 2025

“An Israeli air strike hit our neighbour’s home and Ahmed [Om’s 16-year-old son who is missing] rushed to the scene. Around half an hour later, more Israeli air strikes hit the building, nearby buildings, and the adjacent areas, they were carpet-bombing the area” – Om Ahmed Seyam, 49-year-old Palestinian mother (Middle East Eye 2024).

Canadian financial institutions are making a killing off their investments in war crimes and genocide. Evidently, in the chilling and cutthroat world of high finances there is more than enough dough to spread around (only if that were true for the 500,000 Gazans facing starvation under Israel’s ruthless blockade and the 25,000 people that die from starvation every single day under global capitalism – see Islamic Relief Canada for additional facts and figures on the global starvation crisis). Beneath all the polished financial institution mission statements, all of which rhythm off liberal buzz words such as, “corporate responsibility,” “commitment,” “trust,” “accountability,” “honesty” and “transparency” (Bank of Montreal), lies an unsettling truth: Canadian financial institutions are complicit in war crimes and genocide (Just Peace Advocates 2024).

While financial institutions such as Toronto-Dominion (TD) Bank and Desjardins tout mission statements and visions linked to “enrich[ing] the lives of […] customers, communities and colleagues” and “contributing to the development of communities,” respectively, none of Canada’s “cream of the crop” financial institutions speak to the issue of the Palestinian communities they are helping to destroy and annihilate. In actuality, enriching the lives of “customers” and “communities” can be accurately translated into enriching the pocketbooks of weapons manufacturers through the process of aiding and abetting Israel’s ongoing genocide. According to Just Peace Advocates (2024), Canadian banks are systemically fueling the dispossession of Palestinian land all of which “has been allowed to take place via regulatory inactivity and/or complicity with a worldview that subscribes to the ‘Greater Israel’ project of colonization of all of Mandate Palestine” (3).

Alleged war criminal, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, holding a map entitled, ‘The New Middle East,’ at the United Nations in September 2023. Adapted from Common Dreams (2023).

According to Just Peace Advocates (2024), Bank of Montreal (BMO), Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), Scotiabank, Toronto-Dominion (TD) Bank, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) and Desjardins Bank are investing billions in war crimes and genocide. Leading the pack is BMO with an outstanding $120B USD in investments in war crimes and genocide followed by RBC $37B USD, Scotiabank $11B USD, TD $6.8B USD, CIBC $2.1B USD and in last place Desjardins $1B USD. In short, it’s an unapologetic race to the top of the ladder of corporate greed all of which is being conducted at the expense of our Palestinian brothers and sisters.

Research conducted by Just Peace Advocates reveals that these morally bankrupt financial institutions are deeply invested in a long list of weapons manufacturers who are providing Israel with their high-tech means of destruction. For instance, BMO has nearly $500M USD invested in Elbit Systems, which provides the Israeli military with 85% of its high-tech murderous drones and land-based military equipment (World Beyond War), as well as other weapons merchants including Raytheon (RTX), Northrop Grumman, L3Harris and Honeywell. With respect to Honeywell, American Friends Service Committee reports, “The company’s HG1700 IMU is part of Boeing’s JDAM kits, which turn unguided bombs into [so-called] precise munitions and have been one of the main weapons systems used by Israel in Gaza.” The Friends Service Committee adds, “While Honeywell’s components typically leave no trace at the site of bombing, one Honeywell component was found intact following a June 6, 2024, Israeli airstrike on the UN al-Sardi school in Gaza. The attack killed 40 Palestinians, including 14 children, and wounded at least 74 others.”

Elbit Systems high-tech war propaganda. Adapted from Elbit Systems.

Similarly, RBC is deeply invested in the same culprits plus General Electric and Boeing. With respect to Boeing, World Beyond War reports that they manufacture a wide range of weapons systems – high-tech kits for so-called precision-guided bombs, fighter jets and attack helicopters and missiles – that end up in the hands of Isreal’s genocidal regime. The American Friends Service Committee elaborates, Boeing is “[t]he world’s fifth largest weapons manufacturer [and] manufactures F-15 fighter jets and Apache AH-64 attack helicopters, which the Israeli Air Force has used extensively in all of its attacks on Gaza and Lebanon […].”

Israel’s Boeing made Apache AH-64 attack helicopter. Adapted from The Times of Israel (2017).

Scotiabank is equally invested in Israel’s death dealing action with investments in a host of weapons dealers already mentioned plus companies such as Caterpillar, which have a long track record of home demolitions across historical Palestine. As far back as 2004 Amnesty International reported atrocities such as, “More than 3,000 homes, vast areas of agriculture land and hundreds of other properties have been destroyed by the Israeli army and security forces in Israel and the Occupied Territories […]. Thousands of other houses have been damaged, and tens of thousands of others are under threat of demolition, their occupants living in fear of homelessness. House demolitions are usually carried out without warning, often at night, and the occupants are forcibly evicted with no time to salvage their belongings. Often the only warning is the rumbling of the Israeli army’s US-made Caterpillar bulldozers beginning to tear down the walls of their homes. The victims are often amongst the poorest and most disadvantaged” (1). In addition, American Friends Service Committee reports, “Armoured D9 bulldozers have been crucial for Israel’s ground invasion of the Gaza Strip, accompanying combat troops and paving their way by clearing roads and demolishing buildings.”

Israel’s armoured Caterpillar-made D9 bulldozers. Adapted from Army Technology (2012).

Finally, don’t be fooled by TD’s Clear and Consistent Investment Philosophy, which reads, “Our investment philosophy is a set of coherent principles” – all of which lacks a clear and coherent principle about divesting from war profiteers such as Lockheed Martin (among many of the companies already listed), which is “by far the largest weapons producer in the world [and] brag[s] about arming over 50 countries, including many of the most oppressive governments and dictatorships” (World Beyond War). As reported by American Friends Service Committee, “Lockheed Martin manufactures AGM-114 Hellfire missiles for Israel’s Apache helicopters. One of the main weapon types used in aerial attacks on Gaza […].” The Friends Service Committee adds, “On Nov. 9, an Israeli missile hit journalists sitting near Shifa Hospital in Gaza City. The missile was reportedly a Lockheed Martin-made Hellfire R9X missile, a version of the Hellfire that was developed by the CIA for carrying out assassinations.”

Lockheed Martin-made Hellfire R9X missile. Adapted from Medium (2022).

Arguably, one of the reasons why we don’t see information like this plastered across news headlines is because “Canadian banks contribute about 70 billion Canadian dollars annually to the Canadian economy” and “[t]he majority of Canadians are shareholders in Canadian banks either directly through share ownership or indirectly through indices and mutual funds” (Just Peace Advocates 2024: 2). Expressed as one of the dominant economic imperatives of our time, which embodies the perverse logic of capital: so-called Canadian national and individual interests supersede the interests of our Palestinian brothers and sisters in Gaza. Such moral and political bankruptcy only normalizes and strengths Israel’s genocidal project.

What to do when a large section of the Canadian economy is funded by war crimes and genocide? For some (e.g., Italian and French dockworkers who refuse to load ships full of military equipment headed to Isreal), the answer is clear: organize and take an unapologetic political stance against war crimes and genocide. According to the latest refusal, The New Arab (2025) reports, “The refusal follows reports from investigative French and Irish outlets Disclose and The Ditch, which revealed that a cargo vessel, the ZIM Contship Era, was scheduled to dock at Fossur-Mer to secretly load 14 tonnes of components produced by the French company Eurolinks.” The New Arab adds, “These components, including Eurolink belts used in Negev 5 machine guns, were allegedly bound for Israel Military Industries, a subsidiary of Elbit Systems, one of Israel’s largest arms manufacturers.” Backing the labourers was the outspoken port worker union the General Confederation of Labor (CGT), which stated, “The port of Marseille-Fos must not be used to supply the Israeli army. The dockworkers and port staff will not take part in the ongoing genocide. We stand for peace among peoples and oppose all wars that bring death, misery, and displacement” (as quoted in The New Arab 2025).

Unfortunately, the moral and political clarity exemplified by Italian and French dockworkers and unions such as the CGT (The New Arab Staff 2025) is not widespread enough to shutdown the genocide machine, which begs the question: How long will it take for labour en masse and their respective unions to find the moral compass guiding Italian and French dockworkers? Just imagine the impact BMO’s 53,597 employees (Macrotrends 2024) and RBC’s 97,000 employees (RBC), for instance, would have if they were as politically organized as Italian and French dockworkers. There is absolutely nothing inevitable about the obedience that keeps the machinery of genocide moving forward.

While stereotyping all bank labourers as neoliberal subjects without a conscience would be a clear error, it is also an error to downplay the power of the ideological and material forces emanating from a neoliberal structure bent on propagating the idea that the world “naturally” constitutes “winners” and “losers” and that the pinnacle of human existence is the private accumulation of wealth irrespective of the violence that the process of accumulation induces along the way. The combined forces of neoliberal ideology and the economic coercion that reproduces obedience to an overarching structure that priorities the bottom line over humanistic considerations is indeed a politically paralyzing set of forces. However, such paralysis is not the end of the road. Similar to the dockworkers and the port worker union act of disobedience and solidarity with Gazans, Noam Chomsky observes, “Direct action means putting yourself on the line. That’s true of civil disobedience and many other types of action, which indicate a depth of commitment and clarification of the issues, which sometime does stir other people to do something. That’s what resistance and civil disobedience were always about. In fact, direct action has often been the preliminary to really major changes. Revolutionary changes, in fact” (Black Rose 2013).

Adapted from OnePath Network (2025).

References

American Friends Service Committee. “Companies Profiting from the Gaza Genocide.” American Friends Service Committee, n.d., https://afsc.org/gaza-genocide-companies. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Amnesty International. “Israel and the Occupied Territories.” Amnesty International, May 2004, https://www.amnesty.org/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/mde150402004en.pdf. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Bank of Montreal. “Our Company.” BMO Financial Group, 2005, https://www.bmo.com/bmo/files/images/7/1/7_ENG_COMPANY.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2025.

Black Rose. “Direct Action, Occupy and the Power of Social Movements: An Interview with Noam Chomsky.” Black Rose, 16 April 2013, https://www.blackrosefed.org/direct-action-occupy-and-the-power-of-social-movements-an-interview-with-noam-chomsky/. Accessed 9 June 2025.

Islamic Relief Canada. “World Hunger Facts.” Islamic Relief Canada, n.d., https://www.islamicreliefcanada.org/emergencies/hunger-crisis-appeal. Accessed 6 June 2025.

Just Peace Advocates. “Who’s banking on war crimes and genocide?” Just Peace Advocates, 2024, https://www.justpeaceadvocates.ca/financial-institutions/. Accessed 6 June 2025.

Macrotrends. “Bank of Montreal: Number of Employees 2010-2025.” Macrotrends, 2024, https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/BMO/bank-of-montreal/number-of-employees. Accessed 9 June 2025.

The New Arab Staff. “Italian and French dockworkers refuse to unload ‘Israel-linked ships.’” The New Arab, 5 June 2025, https://www.newarab.com/news/italian-french-dockers-refuse-unload-israel-linked-ships. Accessed 9 June 2025.

World Beyond War. “The exhibitors and attendees at CANSEC are making a fortune off of the carnage in Gaza.” World Beyond War, n.d., https://worldbeyondwar.org/cansec/. Accessed 9 June 2025.

CANSEC 2025: The Architects of War & Genocide Are Back in Town

By: Seek The Alternatives (STA) – Community-Based Grassroots Organization

Wednesday, May 21, 2025

CANSEC certainly qualifies in the aid and abet category of planning for mass murder and repression” (Homes Not Bombs 2003).

Substructures of organized war and genocide: CADSI, CANSEC, EY and many more…

On Wednesday, May 28, 2025, the architects of war and genocide will be back in Canada’s capital city for their annual CANSEC arms fair at the EY Centre located at 4899 Uplands Drive, Ottawa, Ontario. The Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries (CADSI) has been organizing this event since the late 1990s and boasts that “CANSEC has always been a great success, and CANSEC 2025 will once again showcase leading-edge technologies, products and services for land-based, naval, aerospace and joint forces military units” (CANSEC 2025). Alongside CADSI’s triumphant commercial discourse exists Canada’s National Research Council (NRC) that promotes itself as an organization that “conducts research and develops technology for clients and partners, delivering security and defence solutions for air, land and sea operations, and for infrastructure, buildings and intelligence” (Government of Canada 2024).

CANSEC 2025 advertisements.

In addition to Canada’s NRC, which sends experts to CANSEC from Canada’s Aerospace Research Centre, Automotive and Surface Transportation Research Centre, Digital Technologies Research Centre, Ocean, Costal and River Engineering Research Centre, and Quantum and Nanotechnologies Research Centre, organizations such as, Defence Research and Development Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, microgrid testing and training facility in Vancouver, Clean Energy Innovation Research Centre, Department of National Defence, Metrology Research Centre, Defence Research and Development Canada’s Suffield Research Centre, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) and Canadian company Radiation Solutions Inc (RSI), pride themselves on their defence partnerships and enterprises with Canada’s NRC.

Government of Canada advertisement for CANSEC 2024.

While the list of participating organizations is extensive, what would an arms bazaar be without the big corporate winners and sponsors of war and genocide? Some of the big names exhibiting their weapons systems include Elbit Systems, Boeing, General Dynamics, L3Harris Technologies, Lockheed Martin, Colt Canada, Raytheon Technologies and BAE Systems (World Beyond War 2024) – all of which make up a significant portion of the over 280 hi-tech weapons exhibitors. While companies such as Elbit Systems boast about “employ[ing] approximately 20,000 people in dozens of countries across five continents” and accumulating “approximately $1.7 billion in revenues and an order backlog of $22.1 billion” (Elbit Systems 2025) they remain utterly silent on the fact that they supply the genocidal regime governing Israel with 85% of their hi-tech drones and land-based military gear (World Beyond War 2024).

Likewise, Boeing states, “As we innovate and operate to make the world better, each one of us takes personal accountability for living these values and leading the way forward for our teams, our customers, our stakeholders, and the communities in which we live and work” (Boeing 2025), without a single mention of the hi-tech weapons they sell to the far-right extremists that make up Israel’s governing elites. Needless to say, the settler colonial state of Israel relies on a host of companies for the hi-tech equipment that enables them to routinely commit war crimes against Palestinians (World Beyond War 2024). General Dynamics, L3Harris Technologies, Lockheed Martin, Colt Canada, Raytheon Technologies and BAE Systems are all playing the same game, which amounts to spreading technologies of destruction under hollow slogans such as, “It’s In Everything We Do” (General Dynamics), “Moving Fast Requires Trust, and Moving Forward Requires Disruption” (L3Harris), “Ensuring Those We Serve Always Stay Ahead of Ready” (Lockheed Martin), “Connecting and Protecting Our World,” (Raytheon Technologies) and “We Serve, Supply and Protect Those Who Serve and Protect Us” (BAE Systems).

Despite warnings from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (2023) that “pursuing security by means of weapons […] only produce[s] insecurity,” superpowers and their corporate companions continue to plant seeds of devastation and misery around the world. With global military spending sitting at $2.72 trillion in 2024 (Stockholm International Peace Research 2025), it is becoming harder to conceptualize a world free from such depraved logic. As a case in point, Stockholm International Peace Research reports, “Military spending increased in all world regions, with particularly rapid growth in both Europe and the Middle East.” Furthermore, “The top five military spenders [in 2024] – the United States, China, Russia, Germany and India – accounted for 60 per cent of the global total, with combined spending of $1635 billon [$1.6 trillion].”

In addition to the big corporate winners exists a long list of sponsors that exchange their financial assistance and overall support for marketing opportunities and product exposure. Corporate sponsors of the architects of war and genocide include, Accenture, Airbus, Amazon Business, AWS, AutogenAI, Boeing, CAE, Calian, CISCO, Commissionaires 100, Dell Technologies, EllisDon, Google Cloud, Hanwha, IBM, IMP, Aerospace & Defence, Issac, Kongsberg, Leonardo DRS, Lockheed Martin, Manitoulin, Transport, McMillan, MDA Space, Oracle, PWC, Pure Logic IT Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Roshel, RTX, Thales, VisionTec Systems.

In conjunction with such exhibitors and sponsors, CANSEC (2025) prides itself on offering over 50 international delegations, over 1,400 scheduled B2B/B2G meetings in a 200,000 square foot facility owned and operated by those willing to shake hands with the producers of hell on earth. Without a doubt, an annual event of this magnitude brings the owners of the EY facility – the Shenkman Corporation – one step closer to achieving their ultimate objective. In the words of the Shenkman Corporation (2025), “We are strategically aligned with numerous companies seeking investment opportunities in real estate development and operating business around the world. We understand the business of investment capital, recognize opportunity, and value entrepreneurship. We strive to bring them all together in order to maximize shareholder value [emphasis added].” When it comes to the Shenkman Corporation’s business dealings with CADSI their mutual business principle becomes crystal clear: prioritization of profits and entrepreneurial partnerships over the children, for instance, on the other end of weapon-based product lines. As a case in point consider the over “120,000 children killed or maimed by wars around the world across continents since 2005, an average of almost 20 a day” (UNICEF 2023) – that is, a stark figure recorded well before Israel’s most recent onslaught of the Palestinians in Gaza. According to Hussein and Haddad (2025), “Israel kills a child in Gaza every 45 minutes.” Hussein and Haddad adds, “Since October 7, 2023, Israel has killed at least 17,400 children, including 15,600 who have been identified. Many more remain buried under the rubble, most presumed dead.”

Shenkman Corporation’s EY Centre.

Reuters Investigation (2023).

In order to sooth any creeping corporate anxiety pertaining to exhibit space, CANSEC touts a variety of exhibition spaces such as, indoor, outdoor (including premium front of house options), turnkey kiosk packages, premium turnkey booths and prestige anchor spaces. With respect to outdoor exhibition space, CANSEC states, “Located at the rear of the venue, outdoor exhibition spaces offer the ability to display a static exhibit where the sky really is the limit.” CANSEC adds that its venue is the ultimate hotspot for any weapons dealer looking to make a “connection to your next buyer.”

CANSEC’s “prestige anchor space.”

Making sense of the organized violence and misery

Making sense of such bizarre death dealing event requires the recognition that, in the words of Robin Luckham (1984), “manufacturers of warfare are overtaking man and expropriating his culture” (1). Luckham adds, “The armament culture is based on the fetishism of the weapon or, rather, on the fetishism of the advanced weapon system. It arises out of interlinked developments in advanced capitalism, the state and the modern war [and genocidal] system” (1). In the case of weapons dealers such as Boeing, General Dynamics and L3Harris Technologies, for instance, it is the fetishism of the attack helicopters, bombs, missiles and so-called smart bomb kits, artillery ammunition, armoured combat vehicles and hi-tech components for various weapons systems like warships, battle tanks and warplanes (World Beyond War 2024) that form the backbone of Israel’s hi-tech onslaught. Under such system, it is the hi-tech weaponry that is revered versus Palestinian life. The unapparelled brutality and horror spread by Israel’s regime in Gaza, which equates to more than triple the firepower used on the people of Hiroshima in August 1945 (Daily Sabah 2024), would be virtually impossible without the soulless assistance of all the weapons dealers looking to make a quick buck. This is the face of an advanced capitalist system that places the cash cow of the arms industry well before human life. Shame lies not only on complicit and belligerent states, weapons dealers and paralyzed international organizations, but also on an entire civilization that has grown accustomed to such tormented logic. The blood of Gazans seeps through the fingers of a civilization struggling in real time to resist and radically transform an imperialist system bent on leveling anything that stands in its way.

Adapted from NPR News (2024).

Adapted from Xinhua (2023).

Photographer Nikita Teryoshin correctly observes (as quoted in Choi 2024), arms fairs are essentially “oversized playground[s] for adults with wine, finger foods and shiny weapons.” While Luckham and Teryoshin draw attention to the harm, power and pervasiveness of armament culture and the darker side of adult immaturity, respectively, feminist and anti-militarist scholar, Cynthia Cockburn (2012), reminds us, “Gender relations that involve male supremacy, violent hierarchies of men and complicit, compliant or victimized femininities – patriarchy seems to […] be a cause of militarism and war. Not in the same immediate sense as those other causes of war, but present as a root cause, a predisposing factor.” Point being, “despite a few exceptions, it has been men who served and been acknowledged as full members of military services” (Taber 2009: 27) and men who make up the vast majority of executive biographies in the weapons dealers’ hierarchy of power (e.g., executive biographies of Boeing, Raytheon Technologies and Elbit Systems reveal the following gender ratios: 12 men + 3 women, 11 men + 2 women, 12 men + 1 woman, respectively). From a critical feminist lens, the total figures are revealing (35 men versus 6 women) and highly symbolic of a male supremacist force driving Gaza and the world at large deeper into the belly of the beast. As discussed by Kronsell (as quoted in Taber 2009: 28), “Western militaries [and weapons dealers] are prime examples of ‘institutions of hegemonic masculinity’ which historically ‘have exclusively included male bodies and norms of masculinity [which] have dominated their practices.’”

A call to hope and action

As Wednesday, May 28, 2025, rolls around let us be conscious of the fact that “selling weapons ‘like vacuum cleaners’” (Choi 2024) is not a social inevitability, but rather a socio-economic and political choice that must be resisted alongside progressive groups such as Homes Not Bombs (read Homes Not Bombs’ (2003) letter to CANSEC organizers here) and the Raging Grannies, which have been resisting the arms-for-profit event since its inception. More recently, anti-war organizations such as World Beyond War and the Palestinian Youth Movement have taken the front seat in continuing the struggle against north America’s largest weapons bazaar, all of which is drenched in criminal dealers taking full advantage of the lucrative business of war and genocide.

As highlighted in Homes Not Bombs’ 2003 letter to CANSEC organizers, CANSEC is illegal and should be shut down without further delay. In the words of Homes Not Bombs, “We believe you [CANSEC organizers] should know that technically, under the Canadian War Crimes Act, the CANSEC exhibition is an illegal gathering, both by the nature of its visitors and by the nature of the products produced by exhibiting companies” – that is, a legal insight that is just as true now as it was back in 2003. Just as CANSEC exhibitors made a pretty penny off the misery instituted by America and its allies in the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003, they stand to accumulate even more wealth off the misery instituted by Israel’s ongoing genocide. Unfortunately, it appears that “skies the limit” for weapons dealers versus all the Palestinian children that are having their lives systemically cut short.

The UN Special Committee, Amnesty International and International Criminal Court (Jabakhanji 2024) have been crystal clear: Isreal’s actions are consistent with genocide and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defence minister Yoav Gallant must be arrested for alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity. Now, we just need to add the big names powering weapons dealing companies such as, Boeing, Raytheon Technologies and Elbit Systems to the rather short list of alleged war criminals. What about Kelly Ortberg (Boeing President and Chief Executive Officer), Christopher T. Calio (Raytheon Technologies Chairman & Chief Executive Officer) and Bezhalel (Butzi) Machlis (Elbit Systems President and Chief Executive Officer) – after all, Netanyahu and his defence minister’s institution of grand havoc would not be possible without all those involved in the “aid and abet category of planning for mass murder and repression” (Homes Not Bombs 2003).

There is hope. As indicated in Homes Not Bombs’ 2003 letter to CANSEC organizers, “The notorious ARMX weapons fair was eventually forced to leave Ottawa because of public resistance. CANSEC, which we may call Son of ARMX, will hopefully face a similar fate. The only real question is whether CANSEC’s exit will result in bitterness, or arise from a true understanding of why this exhibition, and the industries it represents, must undergo an immediate transformation to stop the spread of injustice and war” – all of which may depend on the strategies and tactics employed by those organizing at the grassroots level. What else will get those caught up in a mass armament culture to realize that the Palestinian bodies saturating Gaza’s soil are so much more than “mannequins or pixels on a screen” (Choi 2024).

Adapted from Pugliese (2016).

Adapted from World Beyond War (2024).

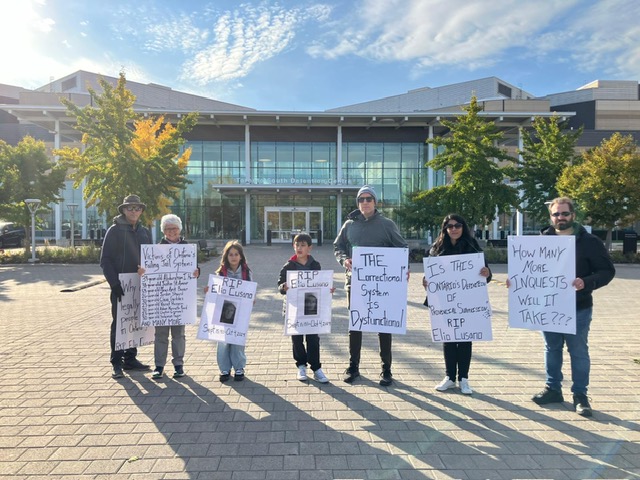

CANSEC resistance in action. Photo taken by Seek The Alternatives (2025).

References

Amnesty International. “‘You Feel Like You Are Subhuman’: Israel’s Genocide Against Palestinians in Gaza.” Amnesty, 5 December 2024, https://amnesty.ca/gazagenocide/. Accessed 21 May 2025.

Boeing. “Our Values.” Boeing, 2025, https://www.boeing.com/sustainability/our-principles#anchor1. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Bulletin. “Moving the Doomsday Clock forward in 1984: Three minutes to midnight.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 27 July 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/07/moving-the-doomsday-clock-forward-in-1984-three-minutes-to-midnight/. Accessed 19 May 2025.

CANSEC. “Canada’s leading defence, security & emerging technology event.” CANSEC, 2025, https://www.defenceandsecurity.ca/CANSEC/. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Choi, Christy. “Selling weapons ‘like vacuum cleaners’: Photographer’s look at the bizarre world of global fairs.” CNN, 24 April 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/24/style/nikita-teryoshin-global-arms-fairs-photo-book. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Cockburn, Cynthia. “‘Don’t talk to me about war. My life’s a battlefield.’” Open Democracy, 25 November 2012, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/dont-talk-to-me-about-war-my-lifes-battlefield/. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Daily Sabah. “Israel hit Gaza with 3 times more firepower than Hiroshima nuke.” Daily Sabah with Agencies, 4 January 2024, https://www.dailysabah.com/world/mid-east/israel-hit-gaza-with-3-times-more-firepower-than-hiroshima-nuke. Accessed 21 May 2025.

Elbit Systems. “Our Story.” Elbit Systems, 2025, https://www.elbitsystems.com/about-us. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Government of Canada. “CANSEC 2024.” Government of Canada, 9 December 2024, https://nrc.canada.ca/en/cansec-2024. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Hussein, Mohamend A. & Haddad, Mohammed. “Gaza’s stolen childhood.” Aljazeera, 26 March 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2025/3/26/gazas-stolen-childhood-the-thousands-of-children-israel-killed. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Jabakhanji, Sara. “International Criminal Court issues arrest warrants for Netanyahu, former Israeli defence minister.” CBC, 21 November 2024, https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/icc-mideast-war-arrest-warrants-1.7389265. Accessed 21 May 2025.

Luckham, Robin. “Armament Culture.” Alternatives Local Global Political, vol.10, no.1, 1984, pp. 1-44. Sage Journals, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/030437548401000102.

Shenkman Group of Companies. “Welcome to Shenkman Corporation.” Shenkman, 2025, https://shenkmancorp.com/. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Stockholm International Peace Research. “Unprecedented rise in global military expenditure as European and Middle East spending surges.” SIPRI, 28 April 2025, https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2025/unprecedented-rise-global-military-expenditure-european-and-middle-east-spending-surges. Accessed 19 May 2025.

Taber, Nancy. “The Profession of Arms: Ideological Codes and Dominant Narratives in Gender in the Canadian Military.” Atlantis, vol. 34, no. 1, 2009, pp. 27-36.

UN Special Committee. “UN Special Committee finds Israel’s warfare methods in Gaza consistent with genocide, including use of starvation as weapon of war.” UN, 14 November 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/11/un-special-committee-finds-israels-warfare-methods-gaza-consistent-genocide. Accessed 21 May 2025.

UNICEF. “More than 300,000 grave violations against children in conflict verified worldwide in past 18 years.” UNICEF, 4 June 2023, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/more-300000-grave-violations-against-children-conflict-verified-worldwide-past-18. Accessed 20 May 2025.

World Beyond War. “The exhibitors and attendees at CANSEC are making a fortune off of the carnage in Gaza.” WBW, 2024, https://worldbeyondwar.org/cansec/. Accessed 20 May 2025.

Critical interventions: Disarming war and genocide from below

By Seek The Alternatives (STA) – Community-Based Grassroots Organization

Wednesday, May 7th, 2025

Adapted photo from: Al Jazeer (2023).

“With her gone, I mourned the dreams we had woven together. Our shared vision of the future, all of it, had crumbled to dust” – 34-year-old psychotherapist named Amani from southern Gaza (read Amani’s full story at UN Women 2023).

The material seeds of war and genocide: Rare earth elements (REEs)

Without access to critical minerals the material forces of militarism and genocide would crumble to the ground. Numerous military systems of destruction such as F-35 fighter jets, so-called smart bombs, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, radar systems, Virginia- and Columbia-class submarines and Tomahawk missiles require great amounts of rare earth elements (REEs). As a case in point, an F-35 fighter jet requires more than 900lbs of REEs, an Arleigh Burke-class DDG-51 destroyer needs roughly 5,200lbs and a Virginia-class submarine requires over 9,000lbs (Baskaran & Schwartz 2025). Similarly, Zadeh (2025) points out, “Defence contractors require stable, secure supplies of these materials for systems ranging from night vision goggles to satellite communications. The Pentagon has identified rare earths as among the most critical materials for maintaining military technological superiority.”

In response to President Trump’s tariff hikes on Chinese commodities, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce is pushing back through a trade approach that effectively weaponizes REEs and magnets – all of which are projected to impair the U.S.’s industrial war base. As discussed by Baskaran and Schwartz, “Further bans on critical minerals inputs will only widen the gap, enabling China to strengthen its military capabilities more quickly than the United States.” As things stand, the U.S.’s REE industry is not prepared to close the increasing gap, which is a problem that the U.S. is attempting to address through the development of domestic capabilities as well as new international partners with REE separation and processing capabilities.

According to Baskaran and Schwartz, “The development of these capabilities is currently underway. In its 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy, the Department of Defence (DoD) set a goal to develop a complete mine-to-magnet REE supply chain that can meet all U.S. defense needs by 2027.” In the process of beefing up domestic capabilities the U.S. will thicken the pockets of REE companies such as MP Materials and Lynas USA who have already received millions from the U.S. government (Baskaran & Schwartz) – that is, a generous amount of funds welcomed with arms wide open, particularly the powerful corporate arms of REE company founders, chairmen, chief executives and shareholders. Panetta (2024), points out that the U.S.’s predicament has resulted in not only a domestic game plan, but also U.S. military cash transfers to Canadian mines. In the words of Panetta, “The U.S. military has, for the first time in generations, spent public money on minerals projects inside Canada: nearly $15 million US to mine and process copper, gold, graphite and cobalt in Quebec and the Northwestern Territories” – all of which form the essential ingredients for a wide range of military-based commodities such as, war planes, drones and munitions. Quebec and the Northwestern Territories are not the only region involved with this death dealing relationship between the U.S. military and Canada. According to Cecco (2024), “The US military has made its largest investment in Canada’s mining sector in decades, spending millions amid a looming battle among nations to control the supply chain of cobalt. […] the Pentagon announced a $20m grant to help build a cobalt refinery in the province of Ontario.” Of course this is nothing new as Canada has a long track record related to feeding the U.S. war machine. As a case in point, the U.S. experienced a major aluminum shortage prior to its jump into WWII and Canada ran to its rescue (Panetta). In the words of Panetta, “American public money flooded into Quebec, building the aluminum industry that supplied raw materials for Allied planes and tanks.”

With respect to today’s global context, it is worth noting that a REE shortage would not only impact the U.S. war machine, but also those that depend on the U.S. for various weapons systems such as the settler colonial state of Israel. As discussed by Gritten (2024), “The US is by far the biggest supplier of arms to Israel, having helped it build one of the most technologically sophisticated militaries in the world.” With respect to Israel’s genocidal fleet of F-35Is, Fabian (2024) reports that the settler state has plans to increase its existing fleet to a total of 75 all of which require the direct involvement of the U.S. government, private weapons dealers such as Lockheed Martin and countless other manufacturers (Gallagher 2025). While the F-35I is said to be a “game-changer” piece of technology for Israel (Fabian), it is important to point out that it will be a “life-changer” for all those who survive its onslaught – all of which remains an impossibility without the essential ingredient of REEs.

Adapted photo from: The Times of Israel (2024).

A toxic mix: Industry, schooling, war and genocide

A simple glance at MP Materials Leadership webpage shows the faces of 9 MP Materials’ Leaders and 7 members on the Board of Directors all of whom appear jubilant – an appearance and feeling that sits completely out of reach for those directly impacted by the instruments of war and genocide that the REE industry helps to manufacture. In the case of MP Materials, it is important to point out that the high levels of schooling James Litinsky, Founder, Chairman & Chief Executive Officer of MP Materials, acquired from Yale, Northwestern University’s School of Law and Kellogg School of Management, failed to translate into even a drop of morality. What to make of a schooling system that pumps out founders, chairmen and chief executive officers that place the accumulation of wealth above the pain, suffering, trauma and death of all those that exist on the other end of the murderous machines that find their material origins in the REE industry? Could it be a mainstream schooling system that caters to the demands of capital? If so, we have a toxic mixture of capitalist industry and schooling that feeds the war and genocide machine behind a veil of empty slogans linked to notions of “inspiring innovation” (Yale), “[…] innovation that makes a difference” (Northwestern University School of Law) and “bring[ing] the future of business into focus” (Kellog School of Management). The question is: What type of “inspiring innovation” is Yale advocating? What type of “difference” is Northwestern University School of Law advocating? What type of “business future” is Kellog School of Management advocating? In the case of Yale, Lacy (2025) provides a clear indication of the type of business they are advocating for. In the words of Lacy, “[…] the university has more than $110,000 invested in military weapons manufacturers and contractors with the Israeli military.” Lacy adds, “The investments include money in funds that hold shares of weapons companies like Raytheon, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin.” Point being, if these schools are advocating for a form of innovation, difference and business that saturates our collective future with more war and genocide it is time for a critical evaluation and restructuring plan built around the principles of nonviolence (versus the principles of capitalist accumulation and unremitting violence). It is time to start individually and collectively imagining and working towards a world filled with industries and educational systems focused on abolishing what The King Centre refers to as The Triple Evils of poverty, racism and militarism, which are “interrelated, all-inclusive, and stand as barriers to our living in the Beloved Community” (ibid).

Of course, top corporate dogs such as James Litinsky are not alone with their pursuits of wealth at any cost. As a case in point, the entire executive committee of Lynas Rare Earths Limited is smiling too! And, in accordance with capitalist-driven passions, they have a good reason to do so. For instance, the reason why Amada Lacaze (Chief Executive Officer), Pol Le-Roux (Chief Operating Officer), Gaudenz Sturzenegger (Director of Finance/CFO), Mimi Afzan Afza (Human Resources Officer), Sarah Leonard (General Counsel) and Daniel Havas (Investor Relations) are all smiling is because Lynas has received approximately US$120 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to establish a first of its kind commercial Heavy Rare Earths (HRE) separation facility in the United States” (Lynas Rare Earths n.d.) – that is, a Rare Wet Dream (RWD) that just came true for the entire executive committee. Let the truth be told: What constitutes a RWD in the west constitutes an all too familiar nightmare for those in the east being bombed on a daily basis without remorse by an administration bent on the complete extinction of Palestinian life and land.

Whether we are talking about MP Materials or Lynas, the main issue here revolves around a capitalist industrial-schooling system that cultivates and operates through a set of social relations best described as morally bankrupt. Any social relations bent on increasing the market value of weapons manufacturers such as, Honeywell International, RTX Corporation, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, L3Harris and Huntington Ingalls, Safran, Dassault Aviation, Thales, BAE Systems, Rheinmetall, Leonardo and Kongsberg Gruppen, is morally bankrupt and ought to be systematically dismantled and repurposed for socially useful projects such as ending starvation all of which kills 25,000 people a day across the globe (Islamic Relief Canada). As discussed by Gonzalez (2024), “The market value of the main military equipment manufacturers in the United States and Europe has skyrocketed over the past two and a half years, in the wake of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.” What to make of an industrial and schooling system working side-by-side to produce the means of governmental death and destruction? When will labour collectively demand that their time, energy and skills be put to humane use? At some point we will recognize that organized labour is more powerful than governmental-corporate power, and conversely, organized governmental-corporate power is more powerful than disorganized labour. With this in mind, it is easy to see that the grand nemesis of any administration bent on war and genocide is an organized labour force that unapologetically says and acts in accordance with the impassioned notion that “enough is enough!” How many more Palestinian lives will it take?

As a specific testament to such moral bankruptcy, consider the focus of James Litinsky’s discourse at MP Materials Q4 2024 Earnings Call in which he states, “[…] we are extremely pleased to maintain strong concentrate product profitability as we expand production and optimize the upstream business.” Litinsky continues, “We remain confident that we will reach gross margin profitability in our midstream operations in the very near term.” Finally, Litinsky adds, “[…] producing high quality magnets for that kind of application demonstrates that MP possesses the intellectual, execution, and production capabilities to be a solution provider for a wide range of critical applications. As the world races to secure the building blocks of physical AI, such as robots, drones or even eVTOL, the United States of America now has a champion, an MP, that can provide a domestic supply chain solution for rare earth magnets” – which forms the foundation of the war and genocide industry.

As demonstrated in these successive quotes, Litinsky’s focus is locked in on notions of “profitability,” “production,” “expansion” and “optimization” versus even the slightest concern for those suffering from the sheer havoc of Israel’s onslaught all of which depends on an REE industry looking to cash in on the havoc. Where is the basic human concern for those suffering on the other end of the supply chain? Where is the basic human introspection that connects the dots between the REE industry and the reprehensible Israeli/U.S.-supported violence against the Palestinian people and their land? What form of schooling and overarching economic logic would give rise to such industrial willingness to shake hands with the demonic forces of war and genocide? The form of schooling in question is crystal clear: capitalist schooling. That is, a soulless form of schooling that teaches, strengthens and normalizes an economic logic bent on “profitability,” “production,” “expansion” and “optimization” over the general welfare of humanity.

Under the current socio-economic arrangement commodities such as the lethal war machines under consideration here (e.g., F-35 fighter jets, “smart bombs,” “Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, radar systems, military submarines, missiles, etc.) get more thought, time, care, attention and planning in comparison to the men, women and children who are expected to miraculously dodge 2000lb bombs dropped from Lockheed inspired F-35s in places like Gaza. While there is plenty of buzz about the labour hours necessary to build F-35As, F-35Bs and F-35Cs (2017 labour hours logged 41,541hrs for As, 57,152hrs for Bs and 60,121hrs for Cs according to Rogoway 2018) there is virtually zero buzz about the unpaid emotional labour hours mothers and fathers will spend grieving the premature death of their children throughout the Gaza Strip and increasingly the West Bank.

As a clear example of capital’s perverse logic at play, Rogoway observes, “[…] what’s most intriguing is just how much these metrics have decreased over time, underlining that Lockheed has found meaningful efficiencies on the F-35 production line in recent years.” Rogoway adds, “Over a five year period of time, the labour it took to assemble a single F-35A dropped by a whopping 62 percent.” Rogoway tops off his uncontainable excitement by stating, “This is a considerable change […] and tells an important story when it comes to the maturity of the F-35’s design compared to 2012.” Like a little boy in a playground that just found out how to throw sand in his “enemy’s” eyes more efficiently, Rogoway is filled with excitement, anticipation and a celebratory tone that glorifies Lockheed’s “meaningful efficiencies.” Only under capital do subjects like Rogoway misrecognize military-industrial competencies and efficiencies with notions of progress. The military-industrial knowhows under examination are anything but progressive. In actuality, such skills and abilities are more accurately described as a means to barbarism. And barbarism is exactly the story that is being squashed under the pro-capitalist military discourse of “intrigue,” “efficiency,” “production” and “design” – concepts that ought to raise a massive red flag for just about anyone who received an education (versus capitalist schooling). Capitalist indoctrination is the name of the game and Rogoway’s discourse is a precise example of just how effective it works. In the shallow words of Rogoway, “The average hours needed for rework and repair of aircraft already delivered is still a major issue […]” – all of which actively conceals the real issue: the reproduction of war and genocide. With all the talk about “the maturity of the F-35’s” one is compelled to ask: When will the capitalist industries and schools that work in unison to create death and suffering around the world mature? In this context, the notion of maturity is not reduced to efficiency; but rather the psychic, spiritual and social growth of a species necessary to abolish local and global capitalist industries and schools of war.

Adapted photo from: TWZ Newsletter.

Here we see the inseparable union of capitalist schooling and industry – that is, a massive production line that pumps out a minority of capital bent founders, chairmen (and women) and chief executive officers as well as a majority of workers equipped with skills they are forced to sell off to companies like MP Materials, Lynas and Lockheed as a means of securing their livelihoods (e.g., food, shelter, clothing, education for their children, etc.). What is MP Materials, for instance, without process engineers, quality assurance laboratory technicians, commissioning support specialists, maintenance planners, financial analysts, industrial electricians, quality control chemists, instrumentation technicians, facilities technicians, manufacturing drafters, wash rack technicians, plant controllers, heavy mobile equipment mechanics and mine crusher operators (MP Materials job posting list)? The short answer: a totally lifeless means of production. Put another way, empty laboratories and fully paralyzed mobile equipment among other forms of “dead” tools and machinery. MP Materials is absolutely nothing without the living and breathing labour it relies on for its continued extraction of REEs.

As Glenn Rikowski (2006) points out, “We, as individuals and groups, are constituted as capital and as labour to differing degrees […]” (8). Rikowski adds, “Because of this, class-in-itself, the active dimension of class then becomes the extent to which individuals and groups identify with their capital and labour aspects of their selves” (8). In translation, the Founder, Chairman & Chief Executive Officer of MP Materials can be conceptualized as a subject that identifies himself with capital (over labour) all while MP Materials’ essential workers such as, process engineers, quality assurance laboratory technicians, commissioning support specialists, etc. identify themselves with labour (over capital). Of course, none of this happens without a capitalist schooling system invested in the process of socially engineering the next generation of capital bent founders, chairmen (and women) and chief executive officers as well as the labour power required to, in the case of MP Materials, separate and process REEs all of which constitute an essential commodity in the process of manufacturing technologies of death and destruction across the world (R.I.P. Tia Mamdouh Mohammed Abu Jazar (female age 0), Bahaa Mustafa Jamal Musa (male age 0), Alma Moamen Mohammed Hamdan (female age 0), Zein al-Din Suleiman Moin al-Najjar (male age 0) and thousands more. See Haddad, Hussein & Antonopoulos 2023 for full list).

Adapted photo from: Jeff Ferry (2024).

The “capitalization of the soul” (Rikowski 2006: 9) is an essential ingredient in the construction and deployment of state sanctioned murder. Without labour power in the form of wash rack technicians, plant controllers, heavy mobile equipment mechanics, mine crusher operators, etc. belligerent settler colonial states such as Israel would fail to acquire genocidal machines such as F-35s all of which require 900lbs of REEs. Put another way, the outrageous death toll in Gaza would never be possible without a morally bankrupt socio-economic system that moves from extraction, manufacturing, distribution, consumption and disposal without any consideration for those that its final death-seeking commodities terminate from the face of the earth (in the case of Gaza over 60,000 since October 7th 2023).

Any moral calculus that attempts to place greater responsibility on the state of Israel versus F-35 pilots or mine crusher operators is a moral calculus attempting to play the illusory game of separation between extraction, manufacturing, distribution, consumption and disposal. Who is responsible for the needless deaths of Layan Mohammed Ismail Salah (female age 1), Hana Moamen Mahmoud Al-Talaa (female age 3), Anas Mohammed Khamis Abu Nimah (male age 6), Bakr Ayman Mohammed Daabes (male age 10) and so on (see Haddad, Hussein & Antonopoulos 2023 for full list of Palestinian deaths)? Based on a morality of separation one might respond, “the higher ups” e.g., Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “genocide Joe” (former U.S.-President Joseph Robinette Biden Jr.), former Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant among other pro-genocidal players; however, based on a morality of inseparability, one might deduce that there are countless “minor” and “major” genocidal players along the entire supply chain. As discussed by Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), evil as we know it is not only orchestrated by “monsters,” but also shallow and thoughtless subjects similar to Adolf Eichmann who lacked the ability “to look at anything from the other’s point of view” (Tommel & d’Entreves 2025). Based on a morality of inseparability one is prompted to reflect on the following questions: Should culpability for the atrocities unfolding before the world’s eyes be reduced to “the higher ups” or should culpability lie with all those who knowingly (or not) collaborate with the genocidal machine at any stage of its development? The difficulty here lies in the acknowledgement that we may all hold some degree of responsibility for what is happening to the Palestinian people – arguably, a moral insight that is much less trivial than one might assume at first glance.

The tension here does not solely rest upon our recognition of degrees of complicity with the onslaught of the Palestinian people and their land, but also our recognition of complicity with a larger social-economic system that uses economic coercion as a means of reengineering the conditions that permit for state-sanctioned murder in the first place. Put another way, REE plant controllers, heavy mobile equipment mechanics and mine crusher operators may in fact be good and informed people caught in the nearly impossible position of working to feed their families versus taking the moral high ground and plummeting into a state of starvation. By most metrics, it can be argued that labour makes rational choices e.g., work and survival over deprivation and death. With this in mind, the grand “enemy” is not labour, which is caught in a seemingly never-ending war of its own, but rather, a social economic system that uses economic coercion to secure its own interests at the expense of everyday people simply trying to survive and provide for their loved ones. With this in mind, one might ponder: Do the forces of economic coercion reduce moral accountability amongst labour? If so, why? Does the threat of joblessness, economic deprivation and downsizing in the short run outweigh the needless pain, suffering and death of thousands of innocent Palestinians? The essential question remains: What will it take to eliminate our individual and collective collaboration with capitalist industry, schooling, war and genocide? Whether it is the extraction phase, manufacturing phase, distribution phase, consumption phase or disposal phase, there are countless labourers involved in moving a commodity (e.g., “smart bomb”) from A-Z – that is, a force, if properly organized that could put a complete stop to any commodity of death moving along the industrial base of war. There is an alternate way and it revolves around disarming war and genocide from below.

At some point we will realize that the blame game and quantification of responsibility is an insufficient moral calculus to bring war and genocide to an end. What we require is a critical awareness, mass rejection and radical transformation of a socio-economic structure that permits for the manufacturing of destructive commodities like F-35s, “smart bombs” and Predator unmanned aerial vehicles in the first place. While holding the Israeli administration responsible for war crimes is an absolute necessity by normative standards it does not guarantee that Israel as a settler colonial state will not rearm and relaunch yet another onslaught in the near to distant future. Point being, accounts of responsibility rooted in a moral and legal calculus of illusory separation leaves the entire structure that generates the possibility of war and genocide intact, which means it is only a matter of time before the next protracted “defensive war,” “war on terror,” etc. To make matters more complex it is important to ponder the ways in which international institutions such as the United Nations employ a moral and legal calculus of illusory separation by attempting to separate the grand crime of war as a socio-historical institution from “war crimes” – that is, a never-ending game of legitimization that feeds into the justifications for a permanent industrial base of war, which ultimately guarantees the existence of war as a means of resolving human conflict.

As a case in point, the United Nations (2024) states, “War crimes include murder, torture, pillage, or intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population, humanitarian aid workers, religious and educational buildings and hospitals. The use of weapons not authorized by international conventions […] can also be considered a war crime.” The problem with this type of normative framework lies in the fact that it attempts to create categories linked to notions of “legitimate” versus “illegitimate” targets (classical euphemism for human beings) and weapons systems, which in effect amounts to an attempt to simultaneously and contradictorily restrain and permit the use of aggression and violence. How can this be? As an international organization bent on promoting “peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet” (United Nations), why not take a firm position against imperialism, empire, war, violence and aggression and work towards shutting down the global machinery of death and destruction for once and for all? Is this too much to ask for from an institution that defines its purpose in the following manner: “To maintain international peace and security, and to that end: to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace, and to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace” (United Nations Charter Article 1).

One possible response to this line of inquiry revolves around the idea that the United Nations must pander to the demands of imperialism, empire and war as a means of retaining its own legitimacy and general functionality. Afterall, the Council on Foreign Relations (2025) states, “The United States has been the largest donor since the body’s founding in 1945.” With respect to fiscal year 2023, “The U.S. government contributed almost $13 billion to the United Nations” (ibid) – all of which makes the United Nations heavily dependent on the U.S. empire (a dynamic of financial dependency that may change with the U.S.’s new status under Trump as a withering empire). Lopez-Claros (2022) points out that if the United Nations stands a chance of retaining its legitimacy in the eyes of the world (versus primary funders and the Security Council) it must fix its voting mechanisms as well as its distribution of power. The call for a United Nations overhaul has been particularly pronounced since Israel’s onslaught of Gaza. For instance, Rahmani (2024) notes that countries such as Iran have been outspoken about the United Nations dive into “dysfunctionality.” According to Rahmani, “Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baghaei has lamented the fact that the United Nations is defeating its purpose and is becoming a dysfunctional platform against Israeli genocide in Gaza.” Lopez-Claros perceptibly notes, “The UN veto power has paralyzed the UN at a time when the multiple global crises we confront call for an effective, problem-solving organization that will enhance our capacity for international cooperation. If it [UN veto power] is not abolished it will not only hamper the organization in its efforts to remain faithful to its noble founding principles, but it will ultimately corrupt its remaining moral authority without which it cannot hope to remain relevant in an interdependent world.”

The grand task: Increasing UN legitimacy through the establishment of universal disarmament

If the United Nations stands a chance of retaining its legitimacy in the eyes of the world it needs to not only (i) reexamine its funding formulas to avoid financial dependency on the U.S. and an unexpected collapse (top ten funders in 2024-2025 of a $5.6 billion budget: United States 26.95%, China 18.69%, Japan 8.03%, Germany 6.11%, United Kingdom 5.36%, France, 5.29%, Italy 3.19%, Canada 2.63%, Republic of Korea 2.57% and Russian Federation 2.29% United Nations Peacekeeping n.d.), (ii) alter its voting mechanisms and (iii) address the problem of power distribution; but also find a way to push its call for universal disarmament to the top of the international agenda. In the words of the United Nations Peace and Security (n.d.), “Disarmament calls for ending the use of all kinds of arms – from firearms to landmines, and from nuclear bombs to chemical and biological weapons. It’s about a safer world. Having fewer arms helps to prevent and mitigate conflict, and reduces terrible human costs.”

Adapted photo from: UN News (2012).

A failure to prioritize universal disarmament with a deep sense of urgency will render the United Nations as an international institution ineffective and contradictory in relation to its global mandate (see United Nations Charter Article 1). As mentioned by the United Nations (n.d.) itself, “World military spending continues to soar. The human and economic toll of violence remains staggering.” The United Nations adds, “Global military spending surged to a record $2.4 trillion in 2023, the ninth consecutive year of growth. In the same year, the economic impact of small arms violence cost $22.6 billion, surpassing official development assistance for education ($14.4 billion) and healthcare ($21.8 billion) in developing countries. Overall, official development assistance in 2023 totaled $223 billion – less than 10 per cent of global military spending.” As pointed out by the United Nations, “Redirecting even a portion of these military expenditures could address critical development challenges, including poverty, economic stability, and inequality.” Steps towards global peace are crystal clear: disarm a heavily militarized globe now and redirect military expenditures towards social issues such as poverty, economic stability and inequality. This is not some romantic leftist dream; but rather, a global necessity that requires the type of coordination and cooperation that governments and industries across the globe already exhibit albeit imperfectly in a multitude of domains e.g., education, healthcare, transportation, housing, etc.

Universal disarmament is not about some reductive debate pertaining to “idealistic thinking” versus “realistic thinking,” it is about morality, politics, practical planning, coordination and cooperation for the sake of a better world for everyone. Either the United Nations’ Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (United Nations n.d.), which places emphasis on “inherent dignity,” “equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family,” “freedom,” “justice” and “peace in the world,” is a sham or a genuine objective. Which is it? As the United Nations stands, it appears like the former; however, there is still time left to prove the latter to a world split along the lines of willful distraction, unremitting doubt and relentless hope followed by coordinated and persistent political action.

Conclusion: Hope and the possibility of a future without war and genocide

While some people and groups around the world might be passively waiting for international organizations like the United Nations to “step it up,” others are unapologetically strategizing, organizing, resisting and hitting the streets as a means of raising awareness and building the political pressure necessary to snap out of the trance of so-called inevitable global militarization, violence, threat, tension and chaos. As a case in point consider the anonymous Google and Amazon workers who condemned Project Nimbus, Microsoft employees calling for No Azure For Apartheid, pro-Palestinian student protesters demanding university divestment from weapons manufacturers and the settler colonial state of Israel as well as mounting Israeli soldiers resisting the ongoing genocide among many other local and global resistance groups.

With respect to anonymous Google and Amazon workers, The Guardian (2021) reports that years before October 7, 2023, 90 labourers at Google and over 300 at Amazon signed an internal letter demanding that the companies end a $1.2 billion contract entitled Project Nimbus and dissolve all links with the Israeli military. In the words of the anonymous workers, “We have watched Google and Amazon aggressively pursue contracts with institutions like the US Department of Defence, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and state and local police departments. These contracts are part of a disturbing pattern of militarization, lack of transparency and avoidance of oversight” (ibid). The letter adds, “Continuing this pattern, our employers signed a contract called Project Nimbus to sell dangerous technology to the Israeli military and government. This contract was signed the same week that the Israeli military attacked Palestinians in the Gaza Strip – killing nearly 250 people, including more than 60 children. The technology our companies have contracted to build will make the systemic discrimination and displacement carried out by the Israeli military and government even crueler and deadlier for Palestinians.” In the same political spirit, Microsoft employees blew the whistle on the company’s ties to Israeli’s hi-tech organized crimes in Gaza. As discussed by Raouf (2025), “Amidst the revelry and celebration of its products, including AI, they were disrupted by two employees [Vaniya Agrawal and Ibtihal Aboussad] representing an organization called No Azure For Apartheid, dedicated to revealing the truth behind that very same AI’s use in Israel’s genocide in Gaza.” Raouf adds, “The Israeli military’s reliance on philanthropist Bill Gates’ Microsoft is so heavy that it’s used in all its major military sectors.” Alongside these absolutely courageous acts of resistance against the ongoing genocide Green (2025) states, “Despite months of fierce pro-Palestinian student protests at scores of college campuses across the country [U.S.] last year, USF [University of San Francisco] and SF [San Francisco State]are among just a handful of schools that have actually agreed to unload certain holdings.” Green adds, “The school’s endowment fund will sell off its direct investments in Palantir, L3Harris, GE Aerospace and RTX Corporation by June 1 [2025], the university confirmed.” Finally, Mednick and Frankel (2025) points out that soldiers such as Yotam Vilk is one “[…] among a growing number of Israeli soldiers speaking out against the […] conflict and refusing to serve anymore, saying they saw or did things that crossed ethical lines.” Mednick and Frankel add, “Some soldiers who’ve refused to continue fighting in Gaza spoke with AP [Associated Press], describing how Palestinians were indiscriminately killed and houses destroyed. Several said they were ordered to burn or demolish homes that posed no threat, and they saw soldiers loot and vandalize residences.”

When it comes to the critical awareness, coordination and political actions of anonymous Google and Amazon workers, Microsoft employees, pro-Palestinian student protesters and outspoken and resisting Israeli soldiers, one thing remains clear: labour contains the capacity to resist and demand changes consistent with promoting and protecting the inherent dignity of all persons. Undoubtedly, process engineers, quality assurance laboratory technicians, commissioning support specialists, maintenance planners, financial analysts, industrial electricians, quality control chemists, instrumentation technicians, facilities technicians, manufacturing drafters, wash rack technicians, plant controllers, heavy mobile equipment mechanics and mine crusher operators working for companies such as MP Materials and Lynas could learn a thing or two from all those who have taken – and continue to take – political action against companies complicit in the settler colonial state-sanctioned murder project conducted by Israel. As discussed by the anonymous Google and Amazon workers, “We envision a future where technology brings people together and makes life better for everyone. To build that brighter future, the companies we work for need to stop contracting with any and all militarized organizations in the US and beyond” (The Guardian) – all of which translates into a clear message for politically idle workers: political imagination precedes political action. If such a political imagination is to ignite and move global labour into action, labour must be aware of a politically paralyzing trap that Henry Giroux (2013) refers to as the “politics of disimagination.” According to Giroux, “[…] the politics of disimagination refers to images, and […] institutions, discourses, and other modes of representation, that undermine the capacity of individuals to bear witness to a different and critical sense of remembering, agency, ethics and collective resistance. Giroux adds that this form of politics “[…] is both a set of cultural apparatuses extending from schools and mainstream media to the new sites of screen culture, and a public pedagogy that functions primarily to undermine the ability of individuals to think critically, imagine the unimaginable, and engage in thoughtful and critical dialogue: put simply, to become critically informed citizens of the world.” If labour can overcome the barrier that the politics of disimagination presents there is no limit to the amount of peace we could collectively enjoy. The question remains: Which will triumph, a politics of disimagination or the “radical imagination” (Giroux) already exemplified by countless progressive workers and students around the world? There is no purely theoretical answer to this question, only a theoretical-practical one that must be critically deliberated and political fought for through the application of sustained political organization and action against the social forces and logics of capital, militarism and genocide.

“In the shadow of this war, the dreams and aspirations of my children have been condensed into a singular, fervent plea: to survive” – 34-year-old psychotherapist named Amani from southern Gaza (read Amani’s full story at UN Women 2023).

References

Baskaran, Gracelin & Schwartz, Meredith. “The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions.” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 14 April 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/consequences-chinas-new-rare-earths-export-restrictions#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20the%20F%2D35,to%20manufacturing%20these%20defense%20technologies. Accessed 1 May 2025.

Cecco, Leyland. “US military announces $20m grant to build cobalt refinery in Canada.” The Guardian, 21 August 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/aug/21/us-military-cobalt-refinery-canada. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Council on Foreign Relations. “Funding the United Nations: How Much Does the U.S. Pay?” CFR.org, 28 February 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/funding-united-nations-what-impact-do-us-contributions-have-un-agencies-and-programs#:~:text=Every%20member%20of%20the%20United,for%20the%20UN%20regular%20budget. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Fabian, Emanuel. “Israel inks deal to buy 25 more F-35 fighter jets for $3 billion.” The Times of Israel, 4 June 2024, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-inks-deal-to-buy-25-more-f-35-fighter-jets-for-3-billion/. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Gallagher, Kelsey. “Global Production of the Israeli F-35I Joint Strike Fighter.” Ploughshares, 30 January 2025, https://www.ploughshares.ca/reports/global-production-of-the-israeli-f-35i-joint-strike-fighter#:~:text=Lockheed%20Martin%20Corporation%20is%20the,supply%20components%20for%20the%20aircraft. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Giroux, Henry. “The Politics of Disimagination and the Pathologies of Power.” Truthout, 27 February 2013, https://truthout.org/articles/the-politics-of-disimagination-and-the-pathologies-of-power/. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Gonzalez, Miguel. “Ukraine and Gaza wars boost the value of major arms manufacturers.” El Pais, 27 August 2024, https://english.elpais.com/economy-and-business/2024-08-27/ukraine-and-gaza-wars-boost-the-value-of-major-arms-manufacturers.html. Accessed 6 May 2025.

Green, Matthew. “USF Divests From Defense Companies Tied to Isreal After Pressure From Students.” KQED, 2 May 2025, https://www.kqed.org/news/12038385/usf-divests-from-defense-companies-tied-to-israel-after-pressure-from-students. Accessed 6 May 2025.

Gritten, David. “Gaza war: Where does Israel get its weapons?” BBC News, 3 September 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-68737412. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Haddad, Mohammed, Hussein, Mohammed & Antonopoulos Konstantinos. “Know their names.” Al Jazeera, 1 November 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/longform/2023/11/1/know-their-names-palestinians-killed-in-israeli-attacks-on-gaza. Accessed 4 May 2025.

Lacy, Akela. “Yale Investments in Companies Selling Arms to Israel Violate State Law, Says an Official Complaint.” The Intercept, 26 March 2025, https://theintercept.com/2025/03/26/yale-endowment-israel-weapons-divest/. Accessed 7 May 2015.

Islamic Relief Canada. “Hunger Crisis Appeal: World Hunger Emergency.” IRC, n.d., https://www.islamicreliefcanada.org/emergencies/hunger-crisis-appeal#:~:text=The%20humanitarian%20needs%20are%20higher,and%20it’s%20only%20getting%20worse. Accessed 6 May 2025.

Litinsky, James. “MP Materials Q4 2024 Earnings Call Transcript.” Quartr, 20 February 2025, https://www.marketbeat.com/earnings/reports/2025-2-20-mp-materials-corp-stock/. Accessed 4 May 2025.

Lopez-Claros, Augusto. “The Origins of the UN Veto and Why it Should be Abolished.” Global Governance Forum, 28 April 2022, https://globalgovernanceforum.org/origins-un-veto-why-it-should-be-abolished/. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Lynas Rare Earths. “Lynas Rare Earths USA: FAQs.” Lynas, n.d., https://lynasrareearths.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Lynas-USA-Fact-Sheet-June-2022.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Mednick, Sam & Frankel, Julia. Some Israeli soldiers refuse to keep fighting in Gaza.” City News, 13 January 2025, https://halifax.citynews.ca/2025/01/13/some-israeli-soldiers-refuse-to-keep-fighting-in-gaza/. Accessed 6 May 2025.

Panetta, Alexander. “What’s behind a historic, unusual U.S. military cash transfer to Canadian mines.” CBC News, 27 May 2024, https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/us-dpa-money-mines-canada-analysis-1.7214664. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Rahmani, Marzieh. “UN becoming ‘dysfunctional’ amid Israeli genocide in Gaza.” Mehr News Agency, 24 October 2024, https://en.mehrnews.com/news/223477/UN-becoming-dysfunctional-amid-Israeli-genocide-in-Gaza. Accessed 5 May 2025.

Raouf, Tariq. “Ex-Microsoft employees blow the whistle on company’s connection to Israel’s AI-driven atrocities.” New Arab, 22 April 2025, https://www.newarab.com/features/ex-microsoft-employees-expose-companys-role-gaza-genocide. Accessed 6 May 2025.

Rikowski, Glenn. “Ten Points on Marx, Class and Education.” Renewing Dialogues Seminar IX, 24 October 24, https://www.academia.edu/6070472/Ten_Points_on_Marx_Class_and_Education?email_work_card=view-paper, p. 1-12. Accessed 4 May 2025.

Rogoway, Tyler. “A Single F-35A According To New Report.” TWZ, 6 June 2018, https://www.twz.com/21367/it-takes-47000-hours-of-labor-to-build-a-single-f-35a. Accessed 6 May 2015.

The Guardian. “We are Google and Amazon workers. We condemn Project Nimbus. The Guardian, 12 October 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/oct/12/google-amazon-workers-condemn-project-nimbus-israeli-military-contract. Accessed 6 May 2025.

The King Centre. “The King Philosophy – Nonviolence365.” The King Centre, n.d., https://thekingcenter.org/about-tkc/the-king-philosophy/. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Tömmel, Tatjana and Maurizio Passerin d’Entreves, “Hannah Arendt”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2025 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2025/entries/arendt/.

United Nations. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” UN, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights. Accessed 6 May 2025.

United Nations Peace and Security. “Disarming our world.” UN, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/peaceandsecurity/disarming-world#:~:text=Disarmament%20calls%20for%20ending%20the,and%20reduces%20terrible%20human%20costs. Accessed 6 May 2025.

United Nations. “Disarmament by the numbers.” UN, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/peaceandsecurity/disarmament-numbers. Accessed 6 May 2016.

United Nations. “Protecting forests for a sustainable future.” UN, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/#:~:text=Peace%2C%20dignity%20and%20equality%20on%20a%20healthy%20planet. Accessed 5 May 2025.

United Nations. “International law: Understanding justice in times of war.” UN, 26 March 2024, https://unric.org/en/international-law-understanding-justice-in-times-of-war/. Accessed 5 May 2025.

United Nations Charter Article 1. “United Nations Charter, Chapter I: Purposes and Principles.” UN, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/chapter-1. Accessed 5 May 2025.

United Nations Peacekeeping. “How we are funded.” UN, n.d., https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/how-we-are-funded. Accessed 6 May 2015.

UN Women. “Voices from Gaza: Amani’s story of loss.” UN, 1 November 2023, https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/feature-story/2023/11/voices-from-gaza-amanis-story-of-loss. Accessed 4 May 2025.

Zadeh, John. “US Rare Earth Miner Halts China Exports Amid Supply Chain Tensions.” Discovery Alert, 18 April 2025, https://discoveryalert.com.au/news/rare-earth-trade-us-china-dynamics-2025/#:~:text=Defense%20applications%20are%20equally%20dependent,guided%20munitions%20to%20radar%20systems. Accessed 4 May 2025.

2025 Earth Day Action: Corporate War Crimes & Honeywell’s Deafening Silence

By: Seek The Alternatives (STA) – Community-Based Grassroots Organization

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

The corporate tactic of perpetual silence